Akira: Pulling on the chains of ransomware

In late June 2023, Stairwell researchers recovered a home directory that had been accidentally publicly exposed from a server conducting exploitation of Fortinet appliances and deploying the Akira ransomware. With this visibility, Stairwell researchers were able to directly observe some key aspects of the tradecraft used by the operators conducting attacks leading up to the deployment of Akira ransomware.

Along with the security research community and the United States Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), we were able to notify multiple companies during the period between when data was exfiltrated by the attacker and their companies being publicly listed on Akira’s data leak site (DLS).

The following report will outline the findings from the recovered data.

Akira

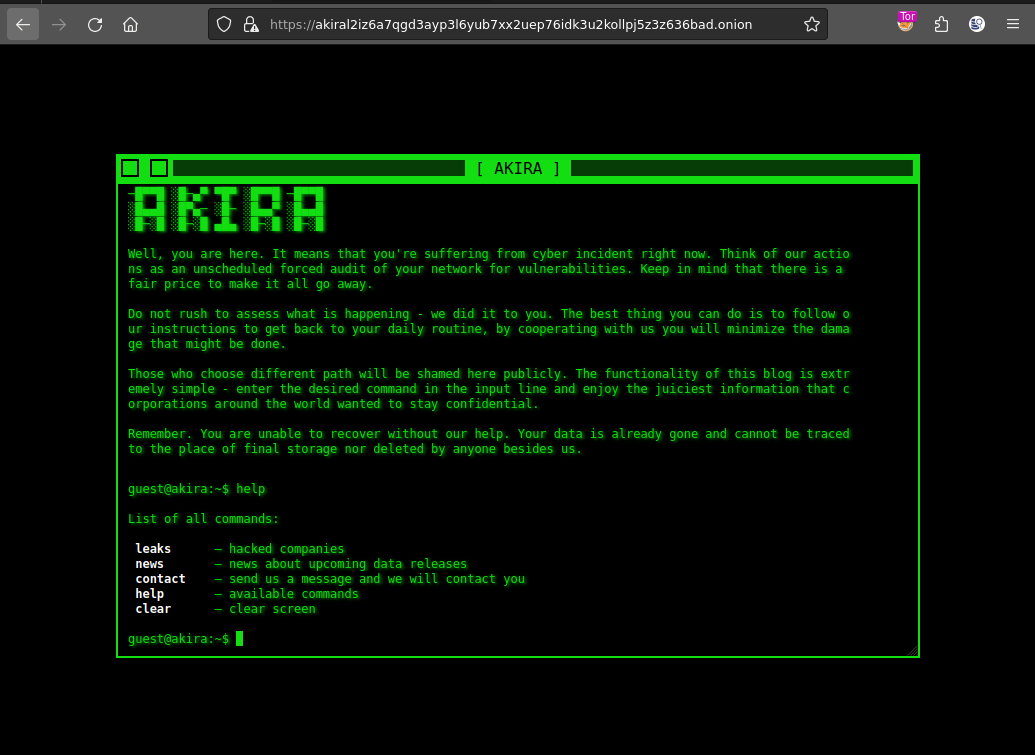

The Akira ransomware group started gaining broad attention in the spring of 2023. Since the launch of their DLS, they have posted 65 different entities that the group has held for ransom (based on counts from our friends at ecrime.ch). In an alert from CERT-IN on 21 July 2023 and confirmed by details covered in this report, Akira ransomware is known to leverage publicly known vulnerabilities in VPN appliances as a means of gaining initial access to a target.

A screenshot of the actor’s data leak site is shown below.

Figure 1: Screenshot of the Akira ransomware blog site.

Technical analysis

The recovered data from the actor system totaled 99 GB and included several stand-alone tools for VPN exploitation and reconnaissance, alongside an aptly named tools directory, containing a collection of open-source pentesting utilities.

From evaluating commands run on the system, this system is assessed to have been primarily used for conducting initial exploitation and exfiltration of data. While the operators of the system installed reconnaissance (such as reconftw) and post-exploitation tools, their usage of these appears limited to testing.

Initial access / exploitation

Within the recovered data were two tools involved in the exploitation of Fortinet devices. Based on the bash_history, the usage of these tools accounted for roughly 11% of the commands executed by the attacker.

The first of these tools was named decrypt.py (SHA256 hash: 44ed99d5516cb7f132016c750cf28a2da39fc0432ed3b7038139f015a589c582) and is used for decrypting password data from Fortinet devices vulnerable to CVE-2019-6693. This script is nearly identical to the original proof-of-concept disclosed on Github; however, this script includes a monitor change for handling string encoding.

The following example illustrates the tool’s usage.

# python3 decrypt.py VegCb7x7j4q9lVhfeYpPifKze4apn7do8EnPOjZWZ2s0iq0LXtd/DfBETgsn4a9CKuoDafVmtsajjwz+Z17W7+MZd+9uf4OCOWeT43dKoZIiEJ4CtyRZaIVNNk3M74g/LqMWH3db8HBMnEv5vKFCU5WaaFNdhGoSm3TEPVrlFkJdzl5MD+83g52w84mOmnoEK3SzJw==

Spring2009!As this tool does not connect to vulnerable devices, the source of the encrypted password data is currently unknown. It’s possible that these encrypted configurations were shared by another operator working in collaboration with the owner of this system.

The other tool identified for exploitation of Fortinet devices was named fortiConfParser.py (SHA256 hash: d626e88d7910048e7f495d8afae49f534e22a90a080f49ca6f5b0b20e8a06c3c). This Python script is used for remotely extracting the configuration of Fortinet devices, using a publicly known authentication bypass (CVE-2022-40684), and decrypting passwords using a reimplementation of the logic from decrypt.py. The following shows an example usage of fortiConfParser.py and the resulting decrypted credentials.

# python3 fortiConfParser.py 10.0.0.1:443

==================================================

[+] LOCAL:

[+]---- adminuser:Summer2023!

[+] LDAP

[+]---- [email protected]:DomainSummer2023!:TDOMAIN:10.0.0.1:sAMAccountName:DC=target,DC=domain

[+]---- [email protected]:DomainSummer2023!:TDOMAIN:10.0.0.1:sAMAccountName:DC=target,DC=domain

Unlike decrypt.py, this tool chains CVE-2019-6693 and CVE-2022-40684 in order to increase the effectiveness of exploitation.

In total, exploitation attempts were observed against 13 IP addresses, of which 9 were able to be attributed to known companies. Geomapping of the IP addresses shows a concentration of US entities.

Figure 2: Mapping of IP addresses to geographic locations targeted for exploitation.

During analysis of the entities targeted by this activity, a consulting company was identified, who had been reportedly attacked in early June by the Snatch ransomware group. As it is common for individual operators to work for multiple ransomware groups, it is possible the operators of this server may not be exclusive to Akira.

Exfiltration

In addition to tooling, the majority of the recovered data from the actor system was encrypted data exfiltrated from three targets of this operator’s attacks. Exfiltrated data is stored in password-protected RAR archives and, based on the command history of the user, was likely encrypted prior to exfiltration by the actor.

In one case, shown below, the actor was observed downloading collected data from a publicly facing server of the targeted network.

Figure 3: Screenshot of command history showing the actor attempting to download stolen data from a public-facing victim server.

Closing

In the initial analysis of the collected data, we had initially attributed this activity exclusively to the Akira ransomware group. As analysis progressed and a target of this activity was identified as a victim of the Snatch ransomware group, we adjusted some of the language used in this report to reflect the reality that ransomware affiliates at times work with multiple different Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) providers.

The ability for individual operators to work across multiple RaaS providers likely supports proliferation of tradecraft and techniques that further enable these types of attacks. In this report, we analyzed a Python tool that chained CVE-2019-6693 and CVE-2022-40684 in order to gain access to Fortinet appliances. While Stairwell has only directly observed this with the Akira ransomware group, it is assessed with medium confidence that intrusions attributed to Snatch and other groups linked to Akira.

As part of analyzing the collected data, Stairwell researchers worked closely with members of the broader cybersecurity community and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) to help notify parties targeted and impacted by this actor. We’re highlighting this as we believe that notifying victims of cyber incidents is the responsibility of those with visibility.